I have OCD. There are no spotless countertops or perfectly aligned rows of color-coded bookshelves (okay, maybe my bookshelves are nicely organized). However, my OCD doesn’t live in the world you can see—it lives in my head. It’s a relentless tangle of ruminations and intrusive thoughts, looping endlessly, demanding answers to questions that have none.

It’s not about being tidy or clean; it’s about control. Not control over my surroundings, but over the chaos running in my head. My compulsions aren’t the kind you notice. They don’t involve washing my hands or flicking a light switch—they’re quieter, covert in its operation. They look like hours of mentally analyzing the same scenario, replaying a conversation in my head, or silently convincing myself that I didn’t say or do something wrong. And even then, the relief—if it comes at all—is only temporary.

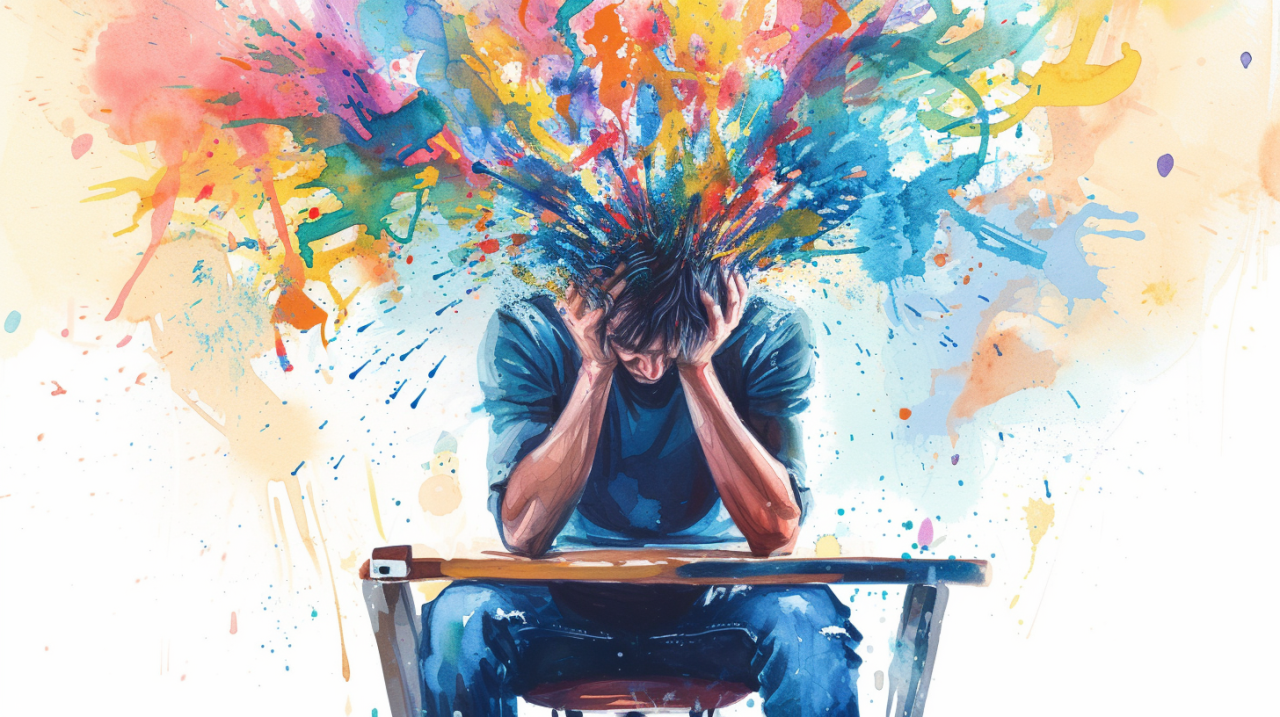

OCD isn’t quirky. It isn’t a personality trait. It’s an invisible storm, one that rages inside me, no matter how calm I may seem on the outside.

Atypical OCD

My OCD is atypical, and that often makes it even harder to explain. It’s not the version people recognize, with visible rituals like checking locks or counting steps. Instead, my OCD is rooted internally—it’s a battle with thoughts that I can’t let go of.

It starts with a single intrusive thought, sharp and unwelcome, slicing through my brain. It could be something small, like wondering if I offended someone in a conversation from weeks ago. It could also be something heavier—a “what if” that spirals into the realm of absurdity. These thoughts feel sticky, clinging to my brain, demanding attention. And I give in—not because I want to, but because the discomfort of ignoring them feels unbearable.

The compulsions that follow are quieter but just as consuming. They’re not physical actions; they’re internal debates, mental checks, endless loops of reasoning that lead nowhere. I’ll replay scenarios, pick apart details, and try to find reassurance in the silence of my own mind. It’s like chasing certainty in a fog, knowing deep down I’ll never catch it but unable to stop running.

This is the reality of my OCD: a relentless need for answers that don’t exist, driven by a fear I can’t understand. It’s exhausting. It’s isolating, made worse by the fact that no one else can see it. And what people don’t see it, they often don’t understand.

The Isolation

Living with OCD that’s mostly internal creates a kind of loneliness that’s hard to put into words. From the outside, I look fine—calm, composed, functional. I can sit through a lecture, chat with friends, or go about my day like nothing’s wrong. But inside, my mind is working overtime, locked in an endless loop of doubt and self-reassurance. No one sees the silent storm brewing in my head.

That invisibility can be the hardest part. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve tried to explain what’s going on in my head, only to be met with confusion or well-meaning but unhelpful advice. “Just don’t think about it,” people say, as if I wouldn’t choose that if I could. I want to tell them that OCD doesn’t feel like something I’m thinking—it feels like something I’m trapped in.

Even with people who care deeply about me, there’s a gap between what I experience and what they can understand. How do you explain that your mind creates fears so vivid they feel real, even when you know they’re not? How do you describe the guilt of wasting hours replaying a single moment, knowing it doesn’t matter but unable to let it go? How do you share the fact that sometimes, it feels easier to stay quiet than to try and make someone else understand?

This is what makes OCD feel so isolating. It’s not just the struggle itself; it’s the fact that it’s so hard to make anyone else see it. And when they can’t see it, they can’t fully validate it—which only makes me gaslight myself more.

Relationships

OCD doesn’t just stay in my head—it seeps into my relationships, turning love, trust, and connection into battlegrounds for doubt and reassurance. It’s not because I don’t believe in the people I love; it’s because OCD makes me question everything, even the things I know to be true.

With my partner, for example, OCD shows up as an endless need for certainty. “Are we good?” I’ll ask, not because she’s ever given me a reason to doubt her, but because OCD insists I ask, again and again. And even when she answers—patiently, lovingly—it doesn’t always feel like enough. I’ll start dissecting her tone, her body language, or even her choice of words, searching for signs of absolute assurance. It’s exhausting—for her and for me.

Then there are the intrusive thoughts, the ones that strike without warning and make me question things I never wanted to question. “What if I’m a bad partner?” “What if I hurt her?” “What if something I said weeks ago was taken the wrong way?” These thoughts are sticky, persistent, and completely at odds with my values and intentions, yet they latch on and siphon my joy like leeches.

The guilt that follows is unbearable. I hate that OCD makes me feel like a burden, that it turns my need for reassurance into something that looks like distrust. I hate that I sometimes pull away, not because I don’t care, but because I’m too afraid of my own thoughts to share them. And above all, I hate the way OCD makes me doubt the very relationships I cherish most.

But amidst the struggle, there are moments of clarity—moments when I remember that OCD isn’t who I am. It’s something I live with, something I’m learning to manage. And in those moments, I’m able to see the love that exists beyond the doubt. I’m able to feel gratitude for the people who stand by me, even when I don’t feel steady myself.

Learning to Navigate OCD

Living with OCD is a journey without a finish line. There’s no “cure” waiting at the end, no moment where the intrusive thoughts magically disappear. Instead, it’s about learning to live alongside it—to recognize its voice, to challenge its power, and to slowly reclaim the parts of my life it tries to steal.

Therapy has been one of the most important tools in this process, particularly Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP). ERP teaches me to sit with the discomfort OCD creates, to resist the urge to respond to intrusive thoughts with reassurance or compulsions. At first, this felt impossible—letting the thoughts linger without “fixing” them went against every instinct I had. But over time, I’ve started to see how this practice weakens OCD’s grip. The thoughts don’t disappear, but they lose their intensity, their ability to control me.

Another lesson I’ve learned is that certainty is a trap. OCD feeds on the illusion that, if I just try hard enough, I can find absolute answers to every question it throws at me. But certainty doesn’t exist—not in the way OCD wants it to. Instead, I’m learning to live with uncertainty, to accept that some doubts will never be resolved and that’s okay. This is one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do, but it’s also one of the most liberating.

Self-compassion has also been essential, though it’s something I’m still working on. OCD can be incredibly cruel, turning my own thoughts against me and making me question my worth. In those moments, I’m trying to remember that OCD isn’t my fault. I didn’t choose this, and I don’t deserve the shame it tries to make me carry. Being kind to myself doesn’t come naturally, but I’m starting to see it as a form of resistance—a way to push back against the narrative OCD wants me to believe.

Navigating OCD isn’t a straight path. There are good days and bad days, moments of progress and moments of setback. But even in the hardest times, I try to hold onto the belief that this work matters. Every time I resist a compulsion, every time I let a thought pass without engaging with it, I’m reclaiming a small piece of my life. And those small pieces add up—they remind me that OCD doesn’t get to have the final say.

A Call for Empathy

I have OCD. It’s not the version you’ve seen in movies or read about in passing—it’s quieter, messier, harder to define. It’s the voice in my head that whispers doubts I never wanted to hear, the loop of ruminations that feels impossible to break. It’s the invisible battles I fight every day, the ones no one else sees but that leave me utterly exhausted.

Living with OCD has taught me so much—not just about the condition itself, but about how deeply misunderstood it is. I’ve learned how easy it is for others to mistake my struggles for quirks, for bad habits, or for things I should just “snap out of.” And I’ve also learned how much compassion can mean, even when someone doesn’t fully understand.

For those who, like me, live with this relentless disorder: I see you. I know how hard it is to explain what’s happening in your mind when even you don’t fully understand it. I know the weight of carrying something invisible, the shame of asking for help, and the strength it takes to keep going. You are not alone in this.

And for those who don’t have OCD: I ask for your empathy. Try to look beyond the stereotypes and see the reality of what we’re experiencing. It may not be visible, but that doesn’t mean it’s not real. Your understanding, your patience, your willingness to listen without judgment—these are gifts that can make an enormous difference.

I’m still learning how to live with OCD, still finding my way through the uncertainty it creates. But what I know for sure is this: OCD doesn’t get to define me. It’s part of my story, but it’s not the whole story. And every day that I face it—messily, imperfectly, but with determination—is a day that I win back. A small act of rebellion—but a liberating one nonetheless.